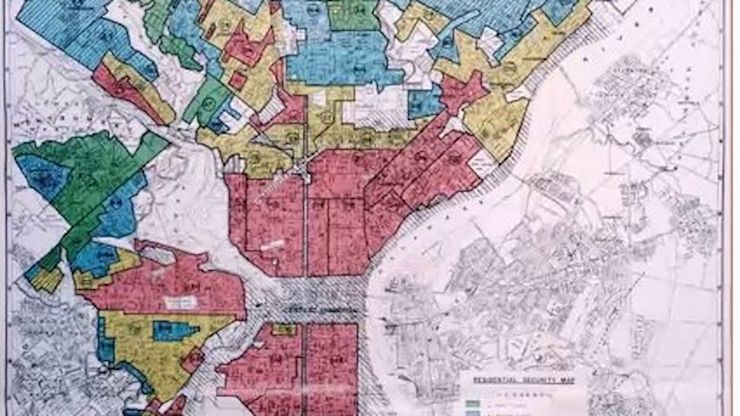

A map of the Philadelphia region showing the red-lined areas that discriminated against minorities from purchasing property in the early to mid-20th century.

In the fifth and sixth installments of the “Racism in America” series, the focus of the conversation pivoted from how racism was founded and became systemic in this country, to how it continues to permeate life today and what can be done to begin to change it.

In her April 14 lecture, “What Laws Were Created in the 20th Century that Further Perpetuated Racism and How Do These Laws Still Impact Us Today?” Lailah Dunbar-Keeys, a sociology adjunct instructor at the Community College of Philadelphia, delved into how racism was proactively created and how it continues to affect American culture.

“What does it mean to be an American?” Dunbar-Keeys posed in her introduction, before

recapping the several hundred years of history that led to slavery, Jim Crow-era oppression, the Civil Rights movement and the modern-day challenges of racism.

“Racism is not just uninformed people against others. It’s a policy that’s become

the foundation. It’s the way we think as Americans because of our culture and conditioning.”

“What does it mean to be an American?” Dunbar-Keeys posed in her introduction, before

recapping the several hundred years of history that led to slavery, Jim Crow-era oppression, the Civil Rights movement and the modern-day challenges of racism.

“Racism is not just uninformed people against others. It’s a policy that’s become

the foundation. It’s the way we think as Americans because of our culture and conditioning.”

Dunbar-Keeys argued that Jim Crow-era policies of the early 20th Century were designed to separate Black Americans into second-class citizens. Following the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision legalizing segregation, Blacks were forced to live “separate but equal” lives from whites.

Yet challenges to these policies from people like Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP led to the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision to desegregate public schools. That landmark case helped launch the Civil Rights movement and ultimately led to President Lyndon Johnson’s decision to sign the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which gives African American people protection to vote.

However Dunbar-Keeys argued it had unintended consequences, too. For example the Voting Rights Act continues to face new challenges every day, as polling stations are routinely closed in predominantly Black neighborhoods across the country, as a way to make it more difficult for residents there to vote.

Similarly, the desegregation of schools launched its own series of events, including a white flight among white Americans, who took their children out of public schools, enrolled them in religious schools and moved out of cities to the newly-built suburbs.

“Research shows when a neighborhood becomes 20 percent people of color,” Dunbar-Keeys said, “white people move away.”

This in turn led to a poorer education among children who remained in urban public schools.

“Property taxes pay for education,” said Dunbar-Keeys. “When real estate taxes are higher, there’s more funding for public schools. The lower the property taxes, the less funding there is going to public schools. White flight changed public schools tremendously.”

This in turn also helped establish a school-to-prison pipeline.

“Not all, but many teachers have lower expectations of African American, Latino, and other children of color. Children may misbehave, get punished and become victims of sort of a one strike you’re out policies that will give young children a record,” said Dunbar-Keeys. “They’ll either be sent to juvenile detention centers or diagnosed and sent to special education. What we know for sure is a large majority of people who find themselves incarcerated are sent to special education, have low reading skills and are high school drop outs.”

In what has been referred to as a “New Jim Crow,” today’s culture has created an image of a Black man as a “brute who is less than human” said Dunbar-Keeys.

“African American people, especially men, are arrested and incarcerated mostly for drug crimes, nonviolent crimes that other people who engage in these behaviors are not arrested and incarcerated for,” she said. “As a result of being incarcerated, they lose the right to vote, the right to live. If they once lived in homes with people who received public assistance, they are no longer able to live there."

Between 1970 and the mid-2000s many Black men were sent to prison for nonviolent offenses. “Now the United States has more people imprisoned than there were enslaved,” she said.

White Privilege

In the sixth “Racism in America” lecture, “White Fragility and White Privilege: Unpacking

the Truth of Racism” Kristen Ostendorf, who previously taught American and Global

History at William Penn Charter School and currently works as a freelance curriculum

writer and consultant, examined the invisible force of racism and how even "nice"

white people perpetuate racism in the United States.

In the sixth “Racism in America” lecture, “White Fragility and White Privilege: Unpacking

the Truth of Racism” Kristen Ostendorf, who previously taught American and Global

History at William Penn Charter School and currently works as a freelance curriculum

writer and consultant, examined the invisible force of racism and how even "nice"

white people perpetuate racism in the United States.

“The system relies on our mistaken belief that only bad people are racist,” she said. “It does not require racist intentions to produce racist outcomes,” quoting Dr. Catherine Kerrison, Professor of History at Villanova University, who led the second and third sessions of the "Racism in America" lecture series

Using the work of Peggy McIntosh, Layla Saad and Robin D'Angelo, among others, Ostendorf unpacked the “invisible knapsacks” of white privilege and fragility in America. The first is the seemingly invisible white privilege in American society, and the second is the defensiveness many white people have around issues of race.

Among the invisible privileges included never being asked to speak on behalf of all white people; someone taking a job without having their credentials or qualifications questioned or others assuming they were a “diversity hire;” or buying a doll from a store and knowing its skin tone will match their own.

After the Civil Rights movement ended, the assumption among white people was that racism was “believed to be individual, conscious and intentional,” said Ostendorf. The root of all defensiveness among whites about racism is that “good people can’t be racist.”

That defensiveness takes many forms including feelings of shame, anger, checking out and trying to change the subject and what Ostendorf described as “nice, white lady tears” that change the subject of racism to comforting the woman crying.

“Nice, white lady tears have been weaponized against Black and brown men for centuries,” she said, noting false accusations of sexual assault and other crimes by crying women have led to lynchings of these men.

By the end of the interactive discussion, participants were able to recognize fragility around racial issues and how, after decades of civil rights activism, racial inequality still permeates in our society.

“Race is a social reality, not a biological reality,” said Ostendorf.

“Racism in America: Understanding the History of Slavery and its Impact on America Culture” is presented by the Richard K. Bennett Lectureship Series, hosted by the Montgomery County Community College Lively Arts Series. The online seven-part series, facilitated by Dr. Fran L. Lassiter, MCCC English Associate Professor, delves deeply into why slavery came into existence and how it was constructed. Each session analyzes the impact of racism and illuminates the efficient systems -- both dejure and defacto -- that were put in place to control and dehumanize African Americans, a system of segregation and discrimination that is threaded deeply into our social system, which still permeates in our society today.

The seventh and final session of the “Racism in America” series is titled “What Are We Doing Today That Continues to Perpetuate Racism and What Can We Do, as a Society, to Proactively Destroy Racism?” Lailah Dunbar-Keeys will close out the series by exploring how our society unconsciously perpetuates racism and examines ways we can proactively destroy racism. By the end of this session, participants will have a better understanding of what perpetuates racism and what we can do help our nation heal.

The online lecture begins Wednesday, May 5 at 12:30 p.m. The event is free and open to the community but registration is required. A Discussion on Race follow-up workshop will be held on Friday, May 14.

For more information, email Lively Arts at [email protected].

Note: Images are courtesy of Lailah Dunbar-Keeys and Kristen Ostendorf from their presentations.